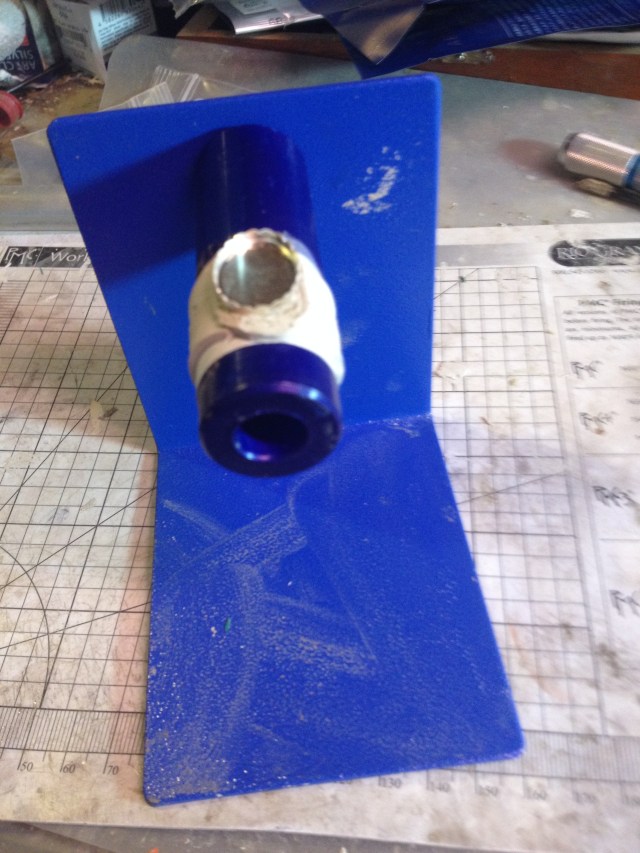

Bezel cups are great. They let you set stones that would never survive the kiln into metal clay, while being much less work than bezel wire. However, they aren’t perfect. Most bezel cups are simply metal cups. Getting them to remain in the clay, while it is being refined or while it is being fired, is a challenge for some. Even if you have mastered getting bezel cups to stay, they still take time. There is an alternative. Metalclayfindings.com makes bezel cups with pronged backings (http://metalclayfindings.com/product/9992316.aspx). That is, they are bezel cups with short prongs in the back that can be inserted into metal clay.

I have recently started using this product, and have been extremely impressed. Getting the bezel cup to stay in the metal clay is a snap — just insert the prongs into the wet clay, let the clay dry, and then fire the piece with the bezel pointed downward. Less time spent with the mechanics of metal clay means more time for the creative aspects! I have only found one minor drawback: the metal clay needs to be at least as thick as the prongs are long, so they don’t stick out the back. If you work 0.75 mm thick, the prongs will not stick out, but will still be visible. If you work 1.0 or more mm thick, the prongs are completely invisible.

What kind of work can you do with this? I’ll provide pictures to illustrate a simple pair of silver earrings with moonstone setting that I recently made.

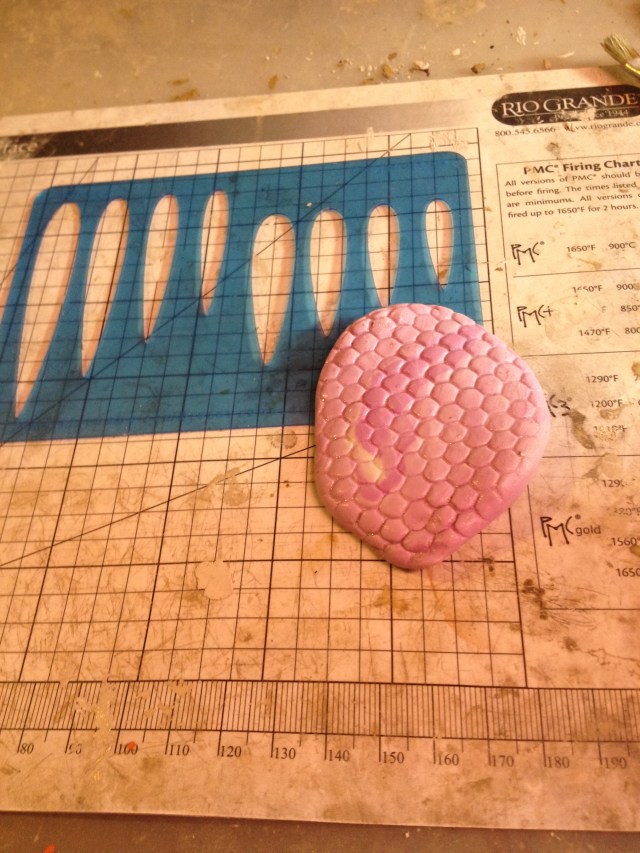

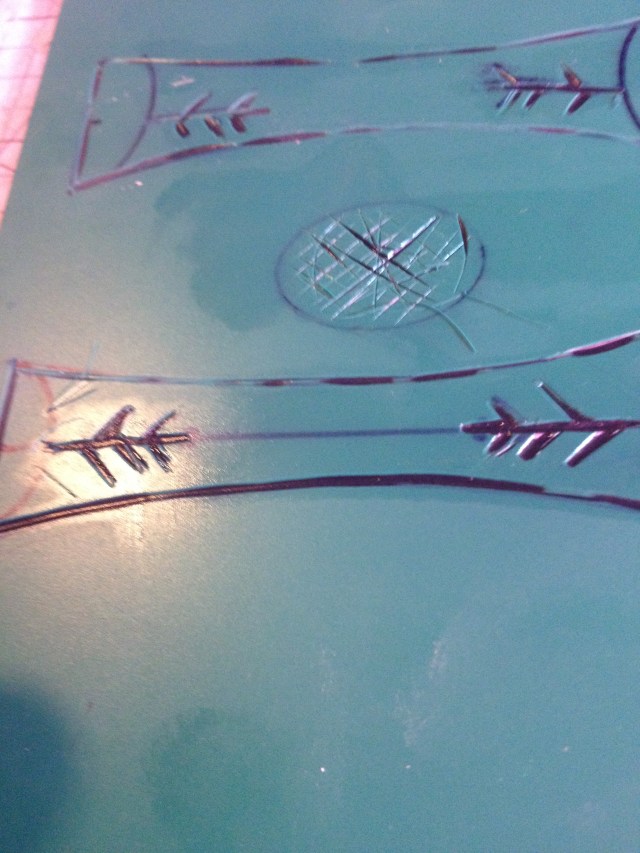

Here are the earrings in greenware. I simply rolled out silver clay to a thickness of 0.75 mm, textured it, inserted the bezel cups, and then cut out the shapes. When the clay dried, I finished it using usual methods. The bezel cups remained firmly fixed, not showing any tendency to move.

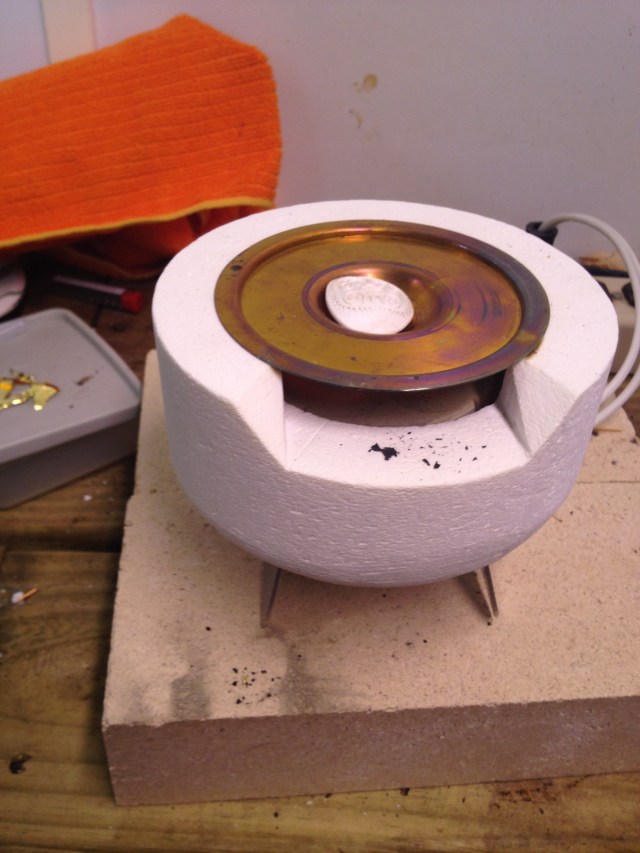

After firing and brushing, I tumbled them.

After tumbling, I patinaed them. I used Maxblack, but, of course, other patinas would be fine.

After tumbling, I patinaed them. I used Maxblack, but, of course, other patinas would be fine.

I then added the moonstones. Using a metal burnishing tool, I bent the edges of the cups to hold the stones.

All that remained was adding the earwires.

All that remained was adding the earwires.

So there you have it. Tabbed bezel cups can make adding non-firable stones a snap. I hope you try it.

So there you have it. Tabbed bezel cups can make adding non-firable stones a snap. I hope you try it.

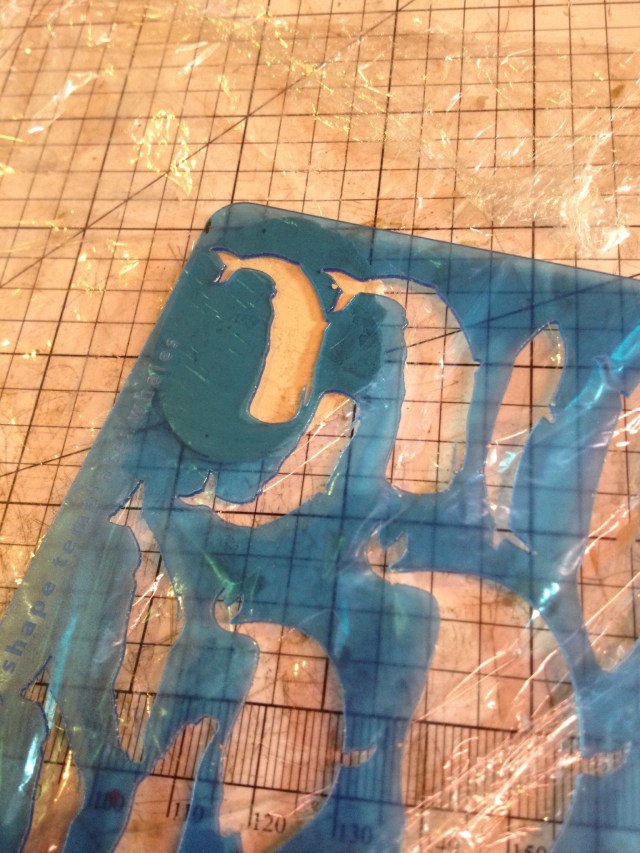

This is what the whale looked like after I trimmed the flash. There is obviously lots of work to do to clean it up, but that comes in the greenware stage.

This is what the whale looked like after I trimmed the flash. There is obviously lots of work to do to clean it up, but that comes in the greenware stage.

This is a silicone pot holder. I found the hexagonal pattern to be quite attractive. I thought I could use it. Of course, nothing I say here is peculiar to this pot holder. You could use any texture you find around the house or in nature that appeals to you — lichens, a clean scrubbing pad, almost anything.

This is a silicone pot holder. I found the hexagonal pattern to be quite attractive. I thought I could use it. Of course, nothing I say here is peculiar to this pot holder. You could use any texture you find around the house or in nature that appeals to you — lichens, a clean scrubbing pad, almost anything.