Acrylic has many virtues as a jewelry element. It magnifies the design beneath it. It sparkles on its own. It allows perishable items, such a dried flowers or seeds, to be incorporated into jewelry. But, best of all, it is highly compatible with metal clay.

The project I will discuss here used silver clay; any other metal clay will work as well. The acrylic I used was Lisa Palevka’s Magic Glos,(http://store.lisapavelka.com/Magic_Glos_s/1869.htm ) a liquid acrylic that hardens upon exposure to UV light. There are other acrylics on the market, some of which do not require a UV lamp to harden. However, my experience is that the UV lamp is worth the extra effort — it produces a harder acrylic, that is less subject to scuffing from everyday wear.

I chose to make a pendant. Earrings work well too. One can even use acrylic in a ring, although such a ring should not be for everyday wear — although acrylic is tough, it can scratch.

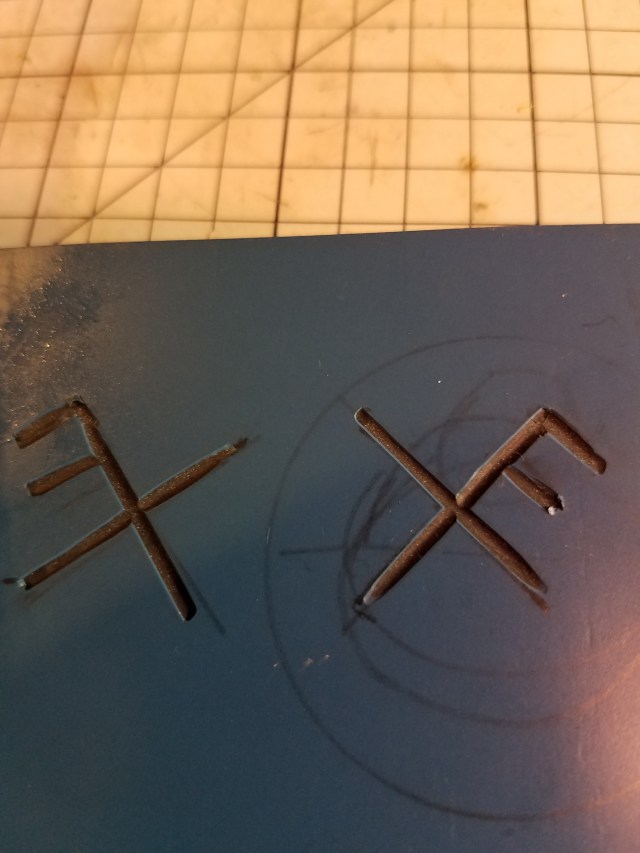

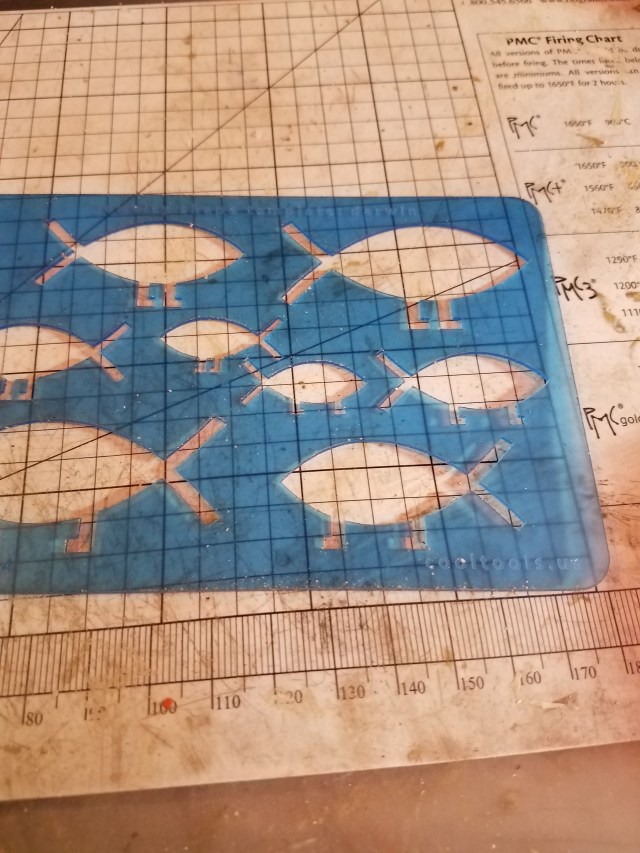

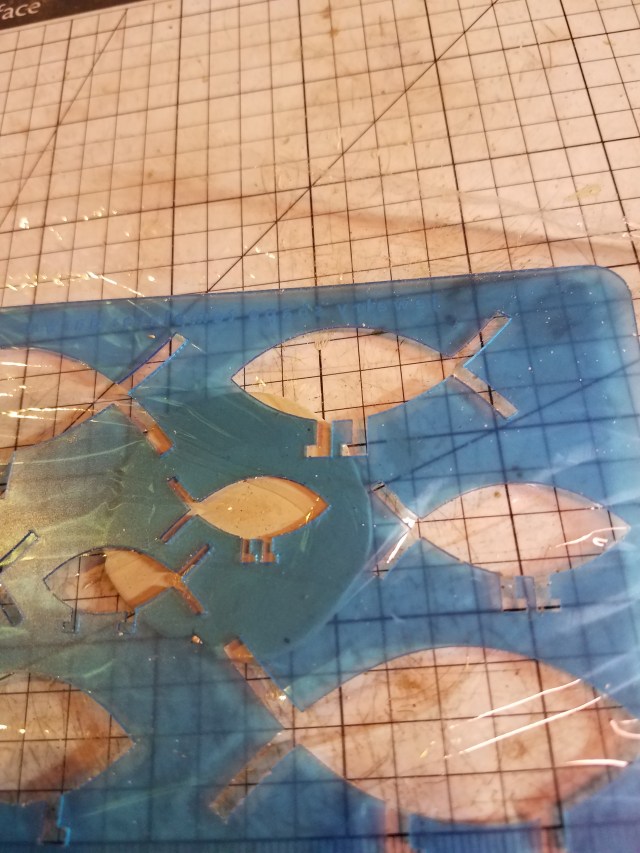

The first step in making my pendant was to cut two shapes from silver clay. The shapes need to be identical, both in shape and size. One needs an opening cut in its middle. That piece is 1.25mm thick; you need the thickness to hold the liquid acrylic, that will be applied later. The other piece can can be thinner (I rolled the silver clay to 0.5 mm).

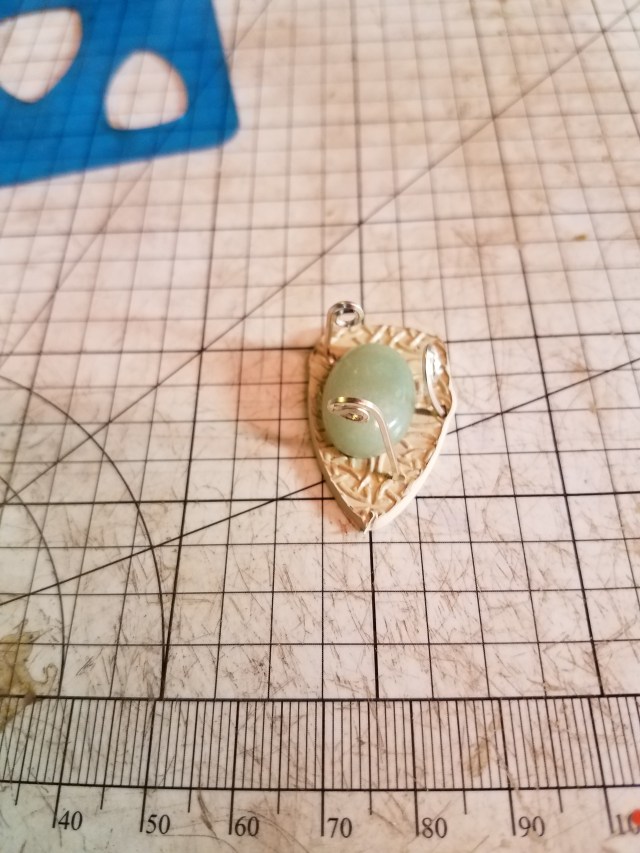

Then one needs to attach the two pieces. I used an embeddable bail, because it allows the piece to lie flat until the acrylic has hardened. If you choose to use some other type of bail, I encourage you to join it in a way that will allow the piece to lie flat. Note that the greenware below has not been finished; there are still rough edges. However, the seams have been sealed. This is important for reasons discussed below.

Then one needs to attach the two pieces. I used an embeddable bail, because it allows the piece to lie flat until the acrylic has hardened. If you choose to use some other type of bail, I encourage you to join it in a way that will allow the piece to lie flat. Note that the greenware below has not been finished; there are still rough edges. However, the seams have been sealed. This is important for reasons discussed below.

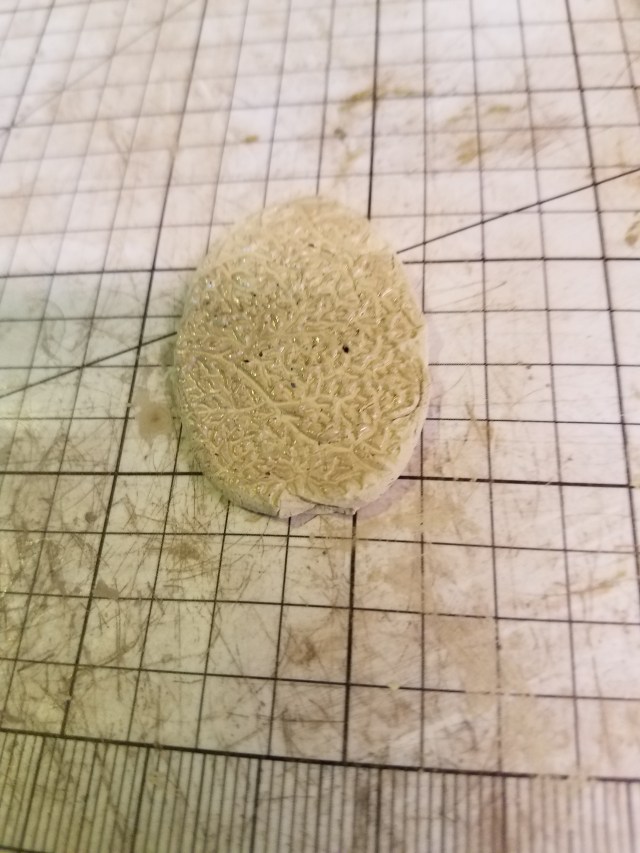

On the surface, it seems that standard greenware finishing techniques are sufficient. In reality, there is a bit more involved. One must carefully make sure that the seams between the two pieces do not show. Even more importantly, one must be sure that the seams are tight enough so that liquid cannot flow through.

On the surface, it seems that standard greenware finishing techniques are sufficient. In reality, there is a bit more involved. One must carefully make sure that the seams between the two pieces do not show. Even more importantly, one must be sure that the seams are tight enough so that liquid cannot flow through.

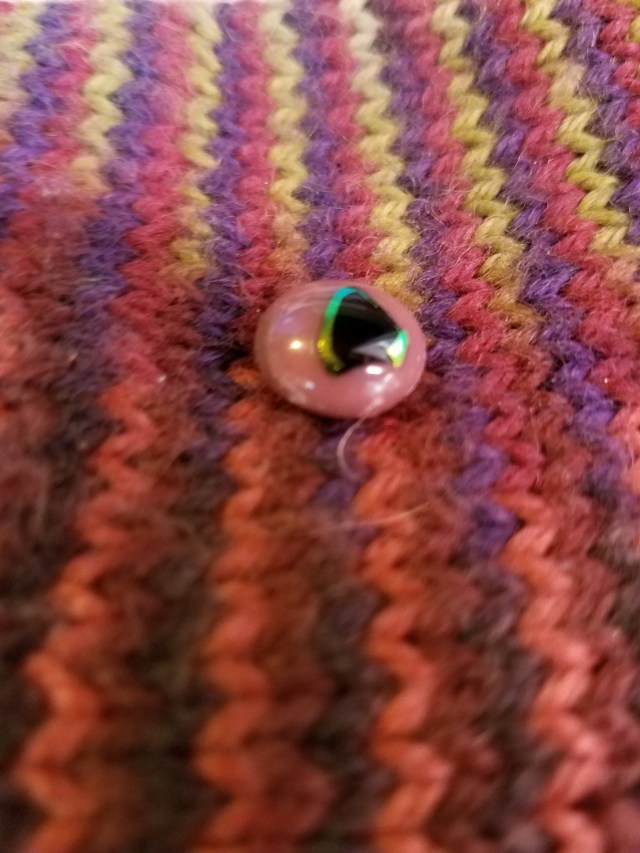

After finishing, the greenware is fired, brushed, and tumbled in the standard way. I used a chip of mother-of-pearl, left over from another project, to be the focal point. Since mother-of-pearl is bright and shiny, I pained the interior black. If you plan on using a dark focal piece, consider painting the interior white or yellow, colors against which a dark focal will show.

It is best to use acrylic paint. There are many forms of coloring that one could use. For example, I have used alcohol inks, although with mixed success. However, I recommend acrylic paint. Acrylic paint is cheap, easy to clean up, and it will not lose or change its color when exposed to UV light.

Finally, during painting, you might get some paint on the outside of the piece. If you do, don’t worry. Acrylic paint can easily be removed with a damp paper towel while it is wet, and with a fine-grained sand paper after it dries.

Now, add whatever you wish to be your focal piece to the well in the silver. As mentioned earlier, I chose a chip of mother-of-pearl. Be sure that the focal piece is completely below the level of the well. If you use something flexible, you can force it down with a toothpick or similar tool. If not, you might have to trim some of it away. By the way, that means that if you use something that will not deform or trim, like a small gem, you must be sure from the first that the well is deep enough.

Once you have done that, decide if you are going to patina the piece. I did not, but there is no reason you can’t. In fact, I have done so on other pieces. However, if you do patina your work, do so before going on to the next stage. Patinas and acrylic might or might not react well, and it is best not to take the change.

Now, put the liquid acrylic into the well. Go slowly, one drop at a time. You do not want to overflow, because removing acrylic, once it has set, is very difficult. In fact, it is acceptable to underfill. After the acrylic has hardened, you can go back and add more acrylic. Acrylic paint will retain its color through many applications of UV light.

When the well is full, expose it to UV light. It is possible to use sunlight, but that takes a long time, and a UV lamp is very fast. However, if you use a UV lamp, do not look at the lit bulb. UV light is potentially hazardous to one’s eyes. I simply cover the lamp with a towel before turning it on, and then turn it off before I remove the towel, which reduces exposure to potentially harmful UV light to almost nothing.

If your acrylic did not harden, or is sticky to the touch, expose it to a bit more UV light (this is rarely needed). If it doesn’t come up to the edge of the well, add some more liquid and repeat the process. Again, be careful to not let the well overflow.

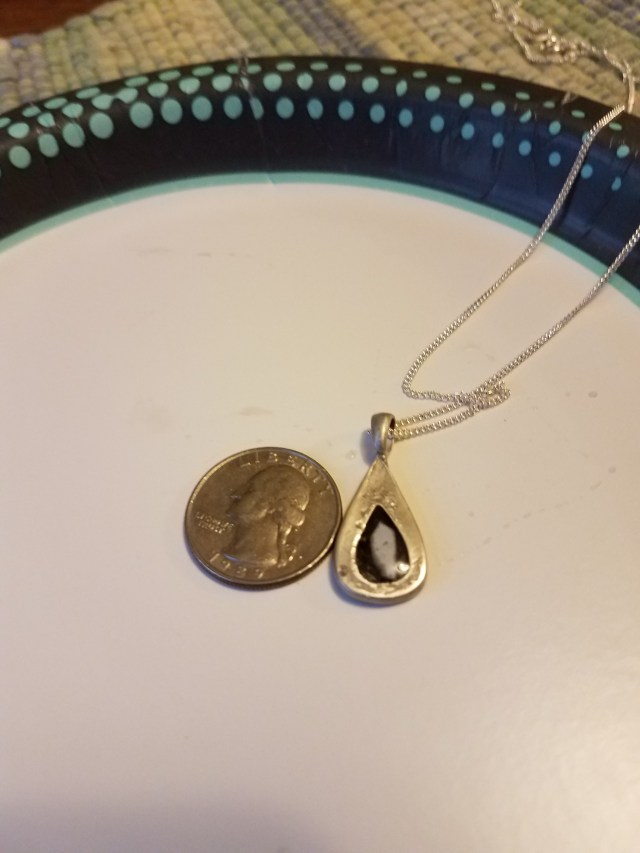

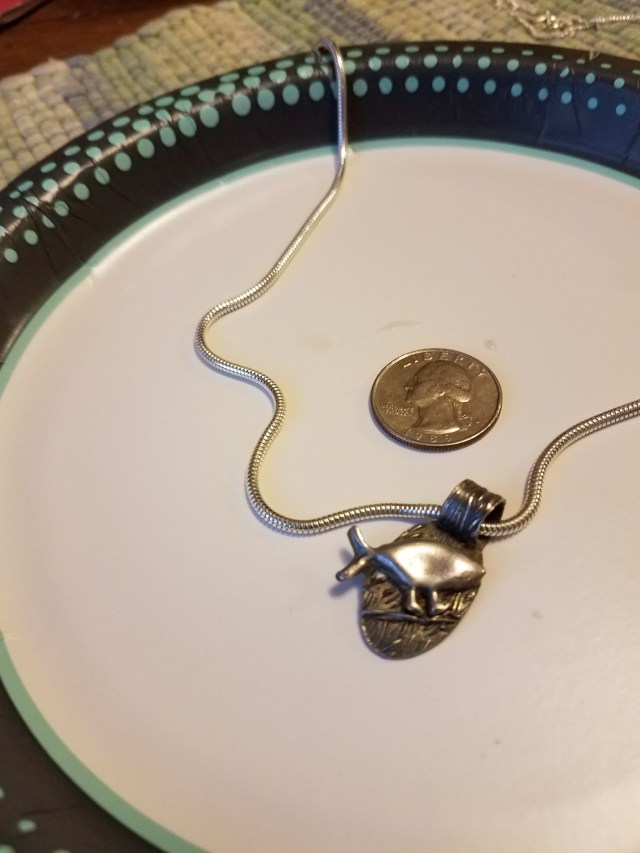

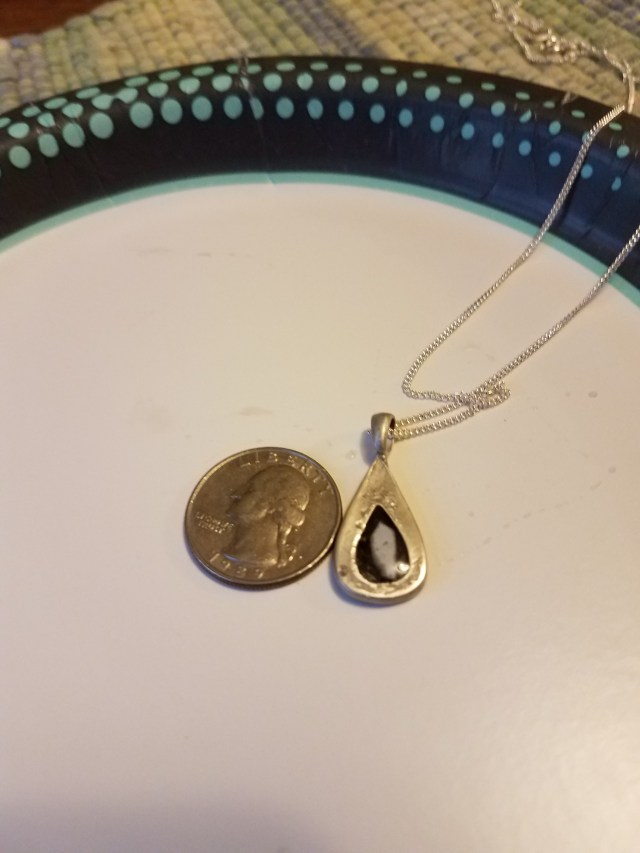

After the acrylic has hardened, you now have your piece. The picture below shows the pendant on a chain. The coin is for scale.

Finally, although I used a chip of mother-of-pearl, do not feel constrained. Many display centers can be embedded in acrylic — dried flowers, seeds, small gemstones. In fact, if one makes a large enough piece, one can even embed a ticket stub from some memorable event.

Finally, although I used a chip of mother-of-pearl, do not feel constrained. Many display centers can be embedded in acrylic — dried flowers, seeds, small gemstones. In fact, if one makes a large enough piece, one can even embed a ticket stub from some memorable event.

I hope this has helped you consider the possibility of using acrylic in your metal clay work. The possibilities are as large as your imagination.

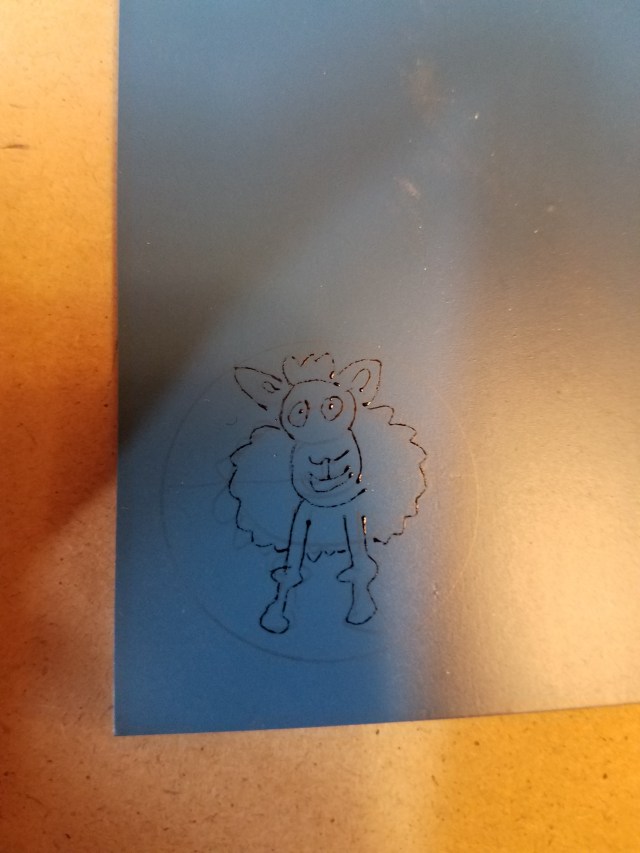

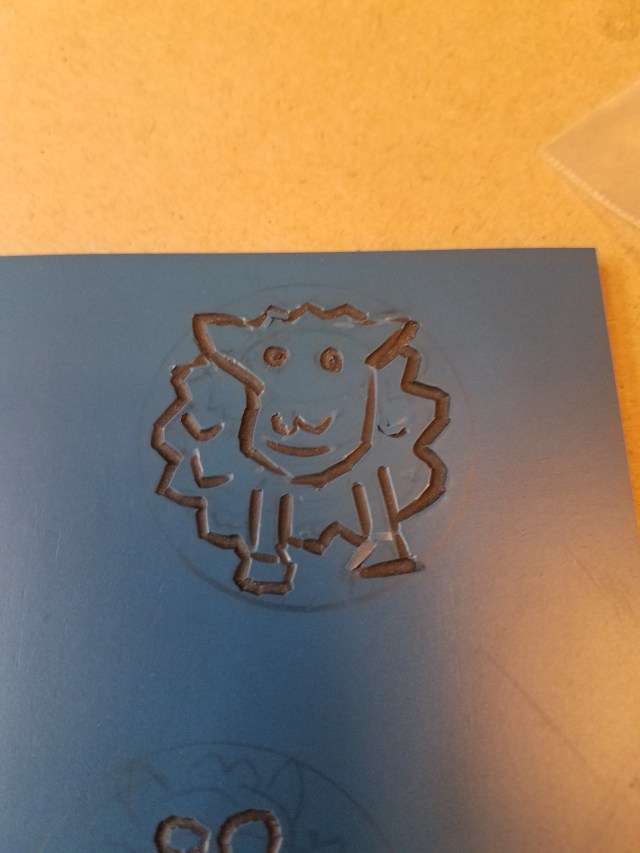

As I said, it would be unethical for me to give step by step directions on how to do basses-taille. However, I hope these pictures have inspired you to seek out someone who can teach you. And, if you have the opportunity to take the class from Pam, she is a wonderful teacher.

As I said, it would be unethical for me to give step by step directions on how to do basses-taille. However, I hope these pictures have inspired you to seek out someone who can teach you. And, if you have the opportunity to take the class from Pam, she is a wonderful teacher.

Then one needs to attach the two pieces. I used an embeddable bail, because it allows the piece to lie flat until the acrylic has hardened. If you choose to use some other type of bail, I encourage you to join it in a way that will allow the piece to lie flat. Note that the greenware below has not been finished; there are still rough edges. However, the seams have been sealed. This is important for reasons discussed below.

Then one needs to attach the two pieces. I used an embeddable bail, because it allows the piece to lie flat until the acrylic has hardened. If you choose to use some other type of bail, I encourage you to join it in a way that will allow the piece to lie flat. Note that the greenware below has not been finished; there are still rough edges. However, the seams have been sealed. This is important for reasons discussed below. On the surface, it seems that standard greenware finishing techniques are sufficient. In reality, there is a bit more involved. One must carefully make sure that the seams between the two pieces do not show. Even more importantly, one must be sure that the seams are tight enough so that liquid cannot flow through.

On the surface, it seems that standard greenware finishing techniques are sufficient. In reality, there is a bit more involved. One must carefully make sure that the seams between the two pieces do not show. Even more importantly, one must be sure that the seams are tight enough so that liquid cannot flow through.

Finally, although I used a chip of mother-of-pearl, do not feel constrained. Many display centers can be embedded in acrylic — dried flowers, seeds, small gemstones. In fact, if one makes a large enough piece, one can even embed a ticket stub from some memorable event.

Finally, although I used a chip of mother-of-pearl, do not feel constrained. Many display centers can be embedded in acrylic — dried flowers, seeds, small gemstones. In fact, if one makes a large enough piece, one can even embed a ticket stub from some memorable event.