There is no shortage of templates, texture sheets, or molds in the metal clay world. One can produce beautiful and, sometimes, spectacular, work using these. However, one day in your metal clay adventure, you will want to move beyond these techniques and into the world of sculpture.

I am going to describe the process I used to sculpt an original bas-relief design in copper clay. The work was inspired by the Tlingit story ‘Raven Steals the Moon’ ( https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Raven_Tales). You can, of course, use similar methods to create any bas-relief you like.

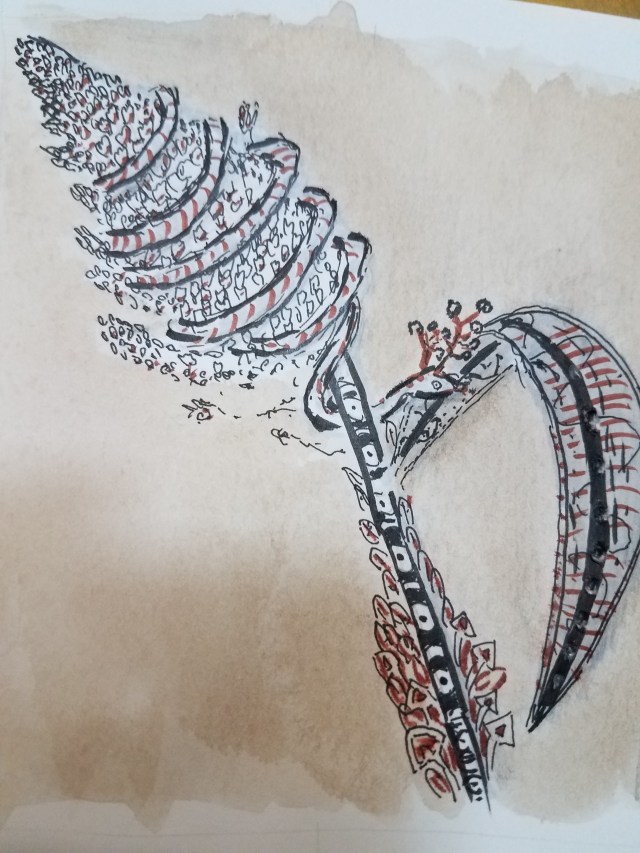

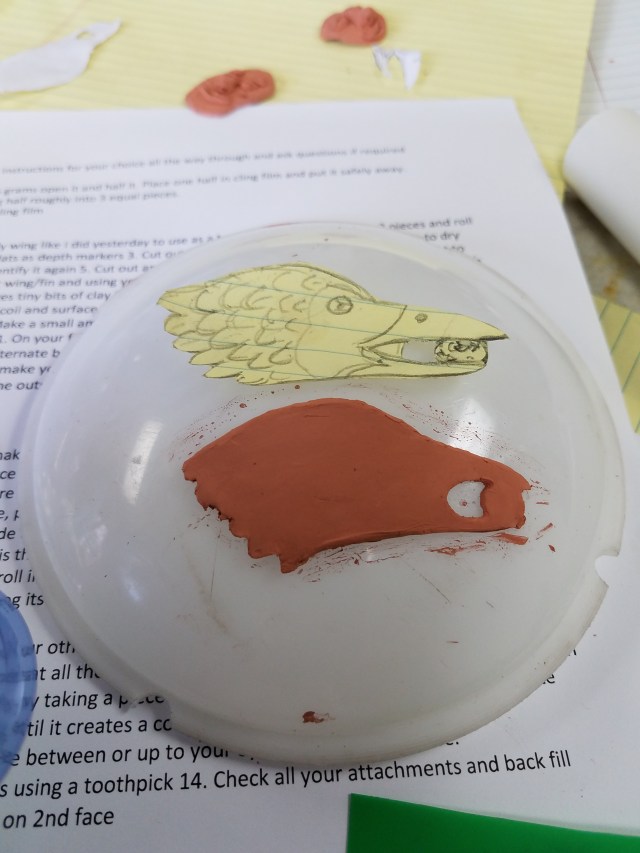

To start with, I drew an image of Raven Stealing the Moon (see below). If you can’t draw, that is not a real handicap. Just use a pre-existing image (although use a public domain image, so you don’t violate someone else’s copyright). If you use a pre-existing image, you might need to change its size with a copying machine, because (except for shrinkage) your final piece will be the size of your original image. Carefully cut your image out with a craft knife, being sure to not leave any jagged edges on the paper. Make copies of the image, less than the number of layers of your bas-relief (Raven is going to have three layers, so I needed two copies in addition to the original).

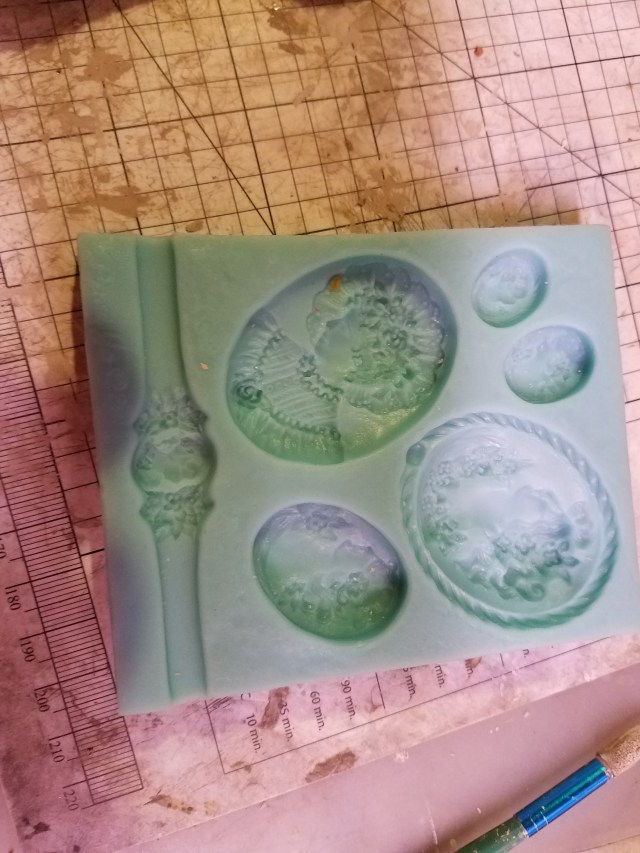

I rolled out the copper clay to 1 mm thick. I cut out the outline of the drawing, using the original drawing as a template. The picture below shows both the original drawing and the outline. The white plastic piece is a dome light, used to the image will not lay flat.

The next step was to cut out a template of the face and beak, 0.75 mm thick. The process was the same, except that I cut away those parts of the copy behind the face. I made an impression where the eye will later go, so there is a place to put the eye. I wanted the moon, in Raven’s beak, to be recessed, so I only included the moon in the first outline.

Then I did the same thing with Raven’s beak. There is an abrupt edge between layers. I did not think that looked good, so I beveled the edges and smoothed a bit with a wet sponge.

Now to make this look like Raven stealing the moon.

Add an eye. Make a tiny sphere of metal clay. Dampen the eye socket and insert the sphere. Roll out three very small snakes of clay. Flatten all three along the edge. Place one atop the eye socket for an eyelid, holding the eyeball in place. Place the second below the eye socket, forming the lower eyelid. Then place the third one atop the upper eyelid (birds have an extra eyelid — you would stop at two if you were making an image of a mammal).

Add feathers. I wanted the feathers to be fairly rough, since ravens tend to ruffle the feathers on the back of their necks when excited. To do this, I made a tiny teardrop of clay. I flattened it and drew a shaft for the feather with a cutting tool. This is one feather. Applying slip, I applied the feather to the back of the raven’s neck. I repeated this process until I had a row of feathers. Then, working from the back forward, I covered the piece with feathers up to the neck. Yes, this is a time consuming process, but the results are worth it. When all the feathers were done, I covered them with a thin layer of slip to smooth them out.

The result appears below.

I attached an invisible bail to the back. The piece has yet to be fired. When it is fired, tumbled, and patinaed, I will show it to you. That will probably be my next post.

In closing, I would like to encourage you to try sculpting. It isn’t has hard as it looks. With a little practice, you can produce truly one-of-a-kind pieces.

Now for the other side.

Now for the other side.

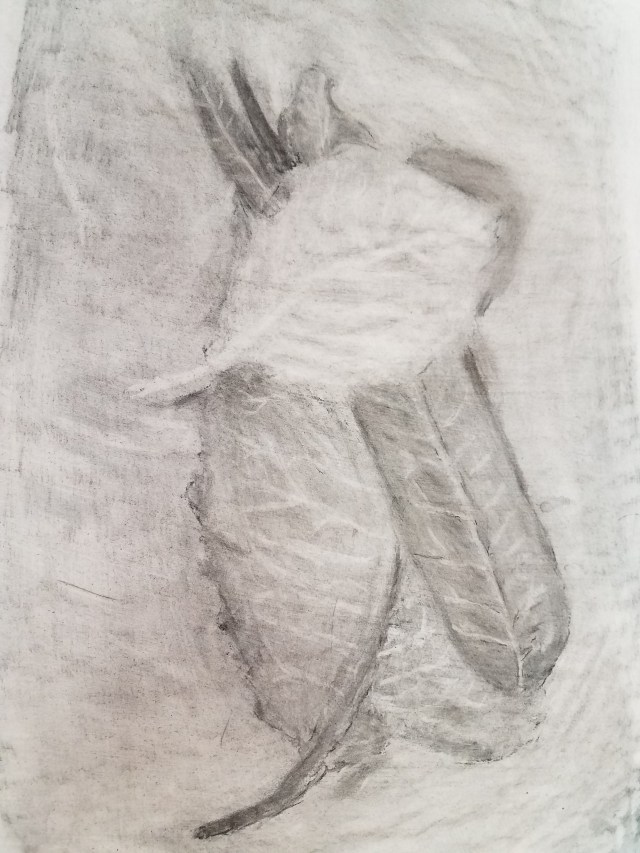

This is the first time I ever tried to do anything with charcoal. Charcoal is, in many ways, the opposite of traditional drawing — one darkens the entire page with charcoal, and then erases to lighten the places where you want the image to be.

This is the first time I ever tried to do anything with charcoal. Charcoal is, in many ways, the opposite of traditional drawing — one darkens the entire page with charcoal, and then erases to lighten the places where you want the image to be. This is literally an exercise — although the instructor liked it so well that she had me matt it. I was told to select nine different colored pencils and then shown a vase containing various plants. The instructions were to spend ten seconds drawing with each color. Then, after that was done, the students were allows to have 90 seconds to clean up their work. If you see fewer than nine colors (and you do), it is because the others were eliminated in the matting.

This is literally an exercise — although the instructor liked it so well that she had me matt it. I was told to select nine different colored pencils and then shown a vase containing various plants. The instructions were to spend ten seconds drawing with each color. Then, after that was done, the students were allows to have 90 seconds to clean up their work. If you see fewer than nine colors (and you do), it is because the others were eliminated in the matting.