Metal clay rings are relatively easy to make — make a band, texture it, dry it on a ring mandrel, add a setting and there you go. However, it is possible to make quite interesting, organic looking sculptural rings.

The rings above are made of silver. They are set, from left to right, with a colorless CZ, a garnet, and a malachite. Each is a basic metal clay ring with some sculptural detail added to give it an organic look. The stone in the ring with the face was deliberately set off-center, to provide visual balance. The other two stones are centered. I will discuss the additions from right to left (so the face, the most technically demanding of the three embellishments I discuss, can come last).

Leaves. Leaves are remarkable easy to make. Using a clay shaping tool (or even one’s fingers), form a small sphere of metal clay. It doesn’t have to be perfect. In fact, it doesn’t have to be very good at all. Then, using one’s fingers, roll one end of the sphere so the whole thing becomes a teardrop. Now flatten it. There you go, instant leaf. It can be made more leaf-like by adding veins. This can be done with a needle tool or by adding small amounts of clay shaped into veins.

Vines. Vines are even easier than leaves. Obtain two small pieces of clean plexiglass. Role a small amount (it will probably take less than you think) of metal clay into a sausage. Place this on one of the pieces of plexiglass. Tilt the other piece at a slight angle. Then roll the metal clay between the two, not too fast and not too slow. As you roll, the clay will transform into a long narrow rope. If the two pieces of plexiglass are parallel, the width of the rope will be constant. If there is an angle, the rope will be narrower at one end than the other. With this narrowing, you wind up with a vine. Pieces can be attached to greenware with slip.

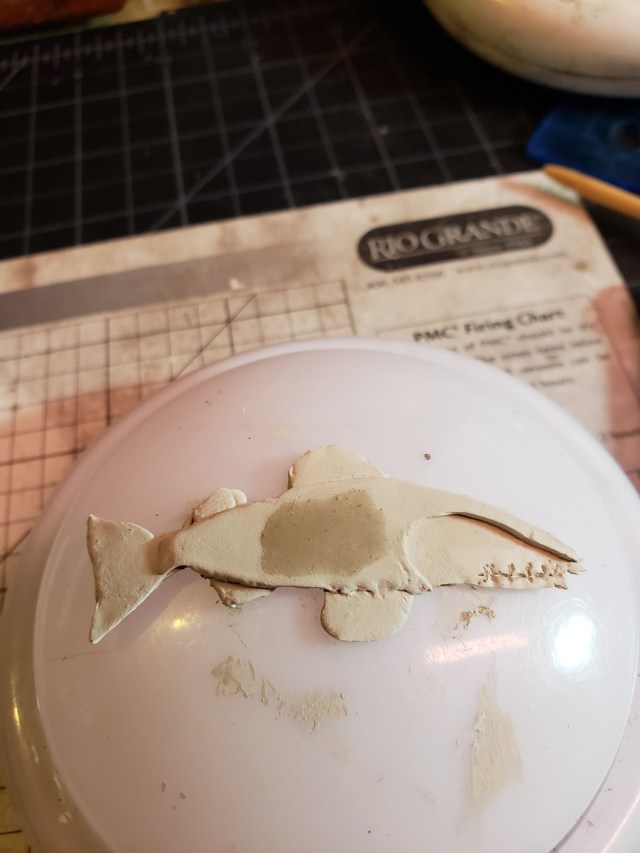

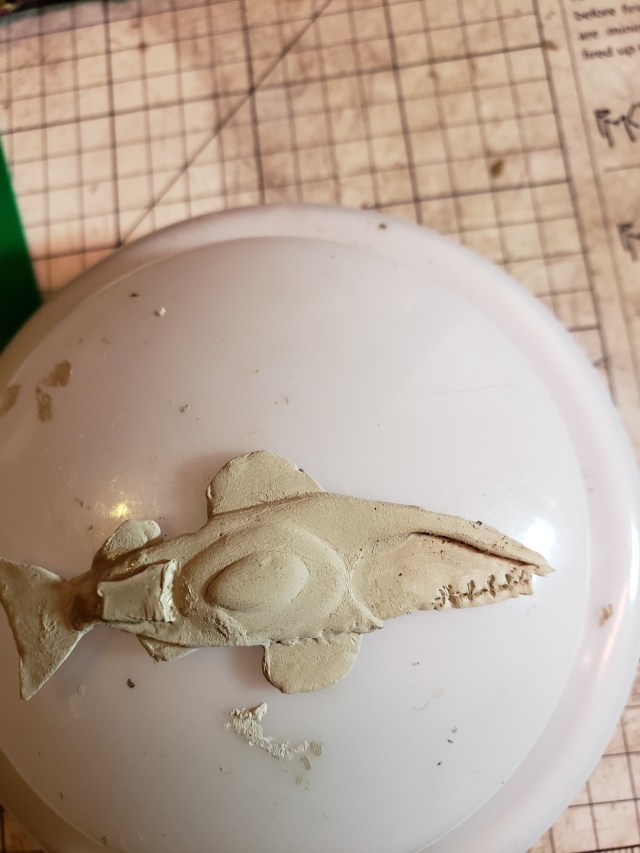

Face. To make a face, have a piece of wet clay where the face it to be located. While I used a rounded rectangle, any shape you choose — circles, triangles, whatever — will work just fine. Using a tool, make two indentations that will eventually be the eyes.

To make the eyes, create two tiny spheres of metal clay, about the same size. Place them in the indentations, attaching with slip. These will be the eyeballs. When the eyeballs dry, make four very small vines (as above). These are then attached to become the eyelids.

If you want bug-eyes, make the spheres larger than the indentations are deep. If you want more normal looking eyes, make them smaller.

To make a mouth, make two more vines, or two ropes. If the two pieces of plexiglass are parallel, you get a rope. If they are angled, you get a vine. Both are fine, although they give you different looks. Attach them with slip to form lips. While it is possible to create teeth, they will not be visible unless the mouth is very wide open. So, if you want teeth to show, make a big, wide open mouth.

Finally, to make the nose, roll a small ‘sausage’ of metal clay. Attach it with slip. When it dries, make two small ovoids of metal clay, flattening one side with a clay shaper. Attach them to the bottom of the ‘sausage’, giving the nose a bulb. If you want to, you can add nostrils using a needle tool or very fine clay shaper.

Finally, as mentioned above, I used a colorless cubic zirconium cabochon in the face ring. Before faceting was common, most stones were cut as cabochons — including diamonds. Diamond cabochons, because they are rarely seen, give your work an exotic look. Real diamond cabochons are, obviously, expensive. However, a transparent cubic zirconium is a remarkable good approximation.

I hope I have inspired you to experiment with sculptural rings. They aren’t particularly difficult to make, and produce some eye-catchingly unique jewelry.