Steampunk is a science fiction sub-genre, a sub-culture, and a style. In short, steampunk fiction is based on the notion of ‘what would have happened if certain technology had been invented earlier than it actually was?’ Think 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea (movie), The Difference Engine (novel), or The Wild Wild West (Movie and TV series). In the subculture, people (among other things) wear clothing appropriate to a Victorian or Edwardian era where technology came much easier. Steampunk style, in addition to be derived from Victorian/Edwardian dress, features images of gears, clock faces, locks and keys. Today, I’m going to talk about how easy it is to make steampunk jewelry.

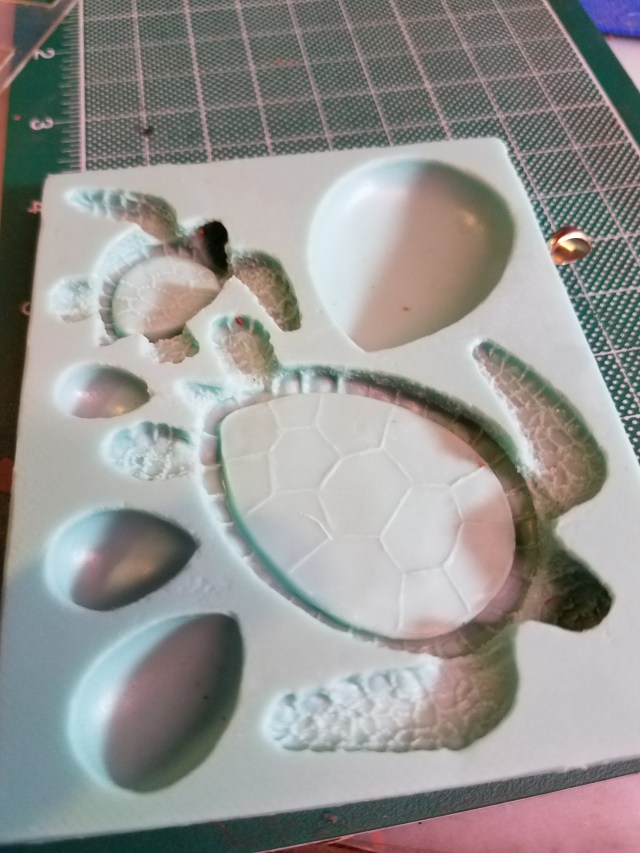

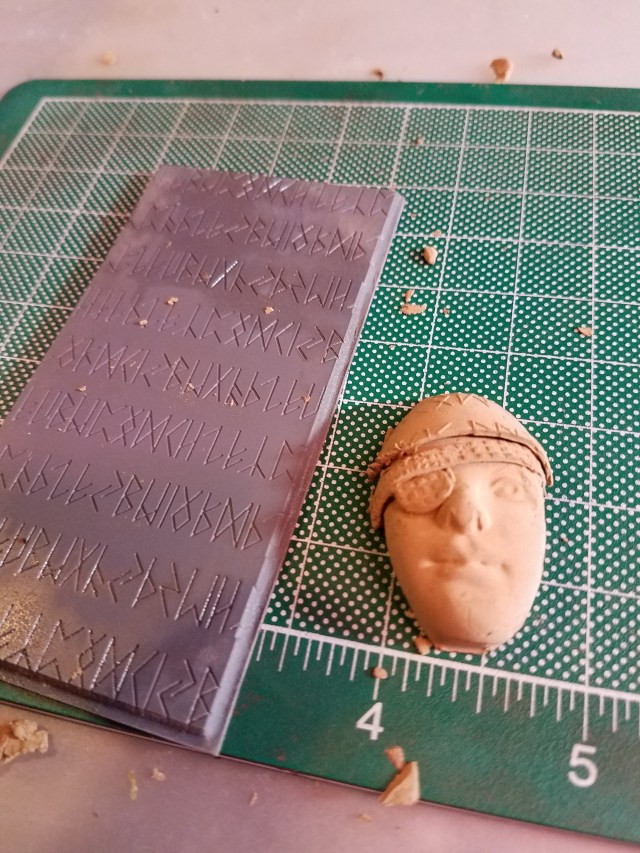

I started out with a mold that contained various steampunk imagery. There are many such molds available. You can either buy one or make you own from two-part molding compound and parts of old clocks.

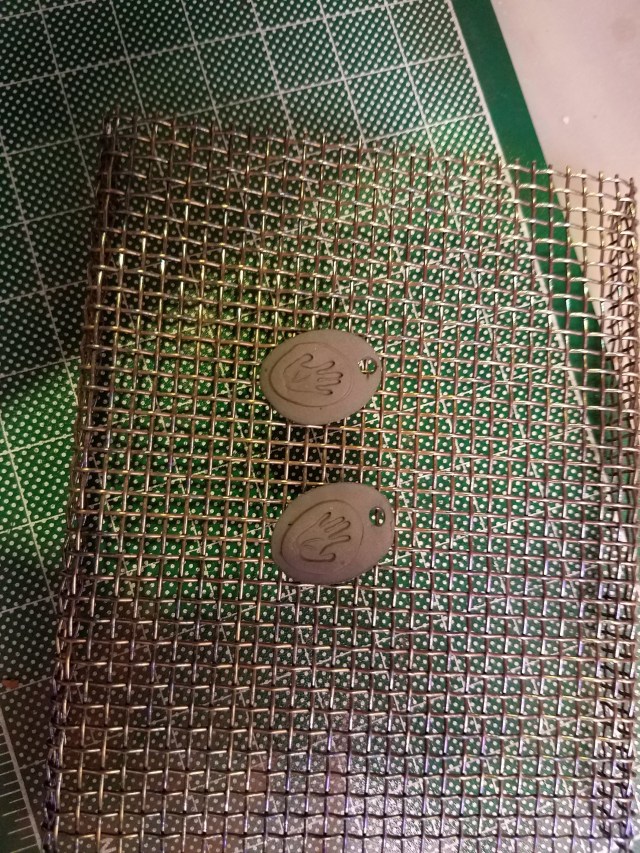

Using standard metal clay technique, I made bronze (some pieces were Five Star bronze, some were Five Star light bronze) versions of two of these images. I made textured geometric backgrounds to attach them to. This resulted in two greenware pendants. To make the pendants a bit more interesting, I drilled a small hole in the bottom of each. Then I made bronze pieces that could been attached to the bottom with a jump ring, allowing the bottom pieces to have some movement. One of these included a bronze bezel cup, the other was just a piece of bronze with gear imagery. I will come back to these pieces in a moment.

For now, I want to say something about what you can do without a mold.

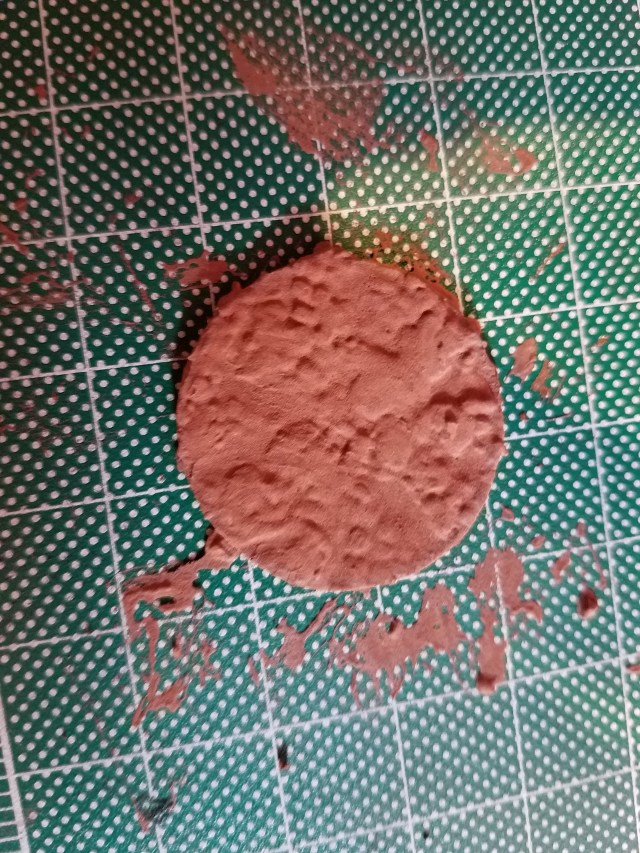

I made a thick (2.5 mm circle) of bronze clay. I cut the center out of it. I then made a thin (0.75mm) circle of the same diameter, and attached it to the back. I wasn’t sure if the inside was or was not going to show, so I textured it. I made a bail that included gears in part of its design.

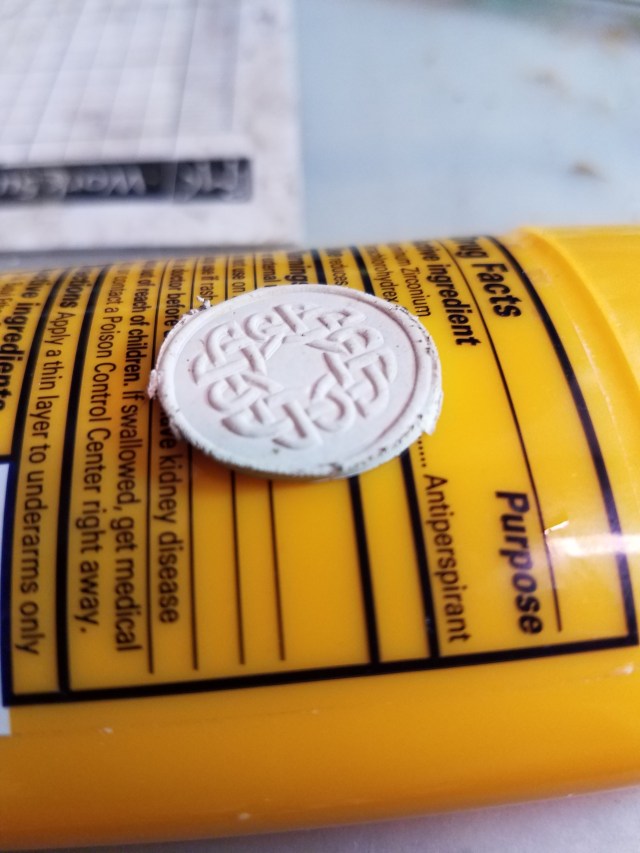

After firing and polishing the three pendants looked like this:

For the piece with the twisted clock face, I simply patinaed and joined the pieces together with a jump ring. All pieces are pictured with a coin to provide scale.

For the piece with the watch workings, I patined the pieces, added a bumble-bee jasper cabochon to the bezel, and attached with a jump ring.

For the open disk, I found a gear from an actual old clock that would fit inside it. Then I encased the gear in acrylic. I used Lisa Pavelka (LisaPavelka.com) acrylic. This acrylic requires UV light to set, but I find it easier to work with than other brands of acrylic.

The essence of steampunk culture is creativity. I hope I have inspired you to try it yourself. Whether you are creating the pieces to wear yourself, for a gift, or to sell, steampunk themes provide many design opportunities. Enjoy exploring them!